A shorter version of this post can be found on the Teachers2Teachers-International Blog: https://t2t-i.org/the-s-in-stem/

In this report, I describe my visit Willam M. Botnan School in Aldea Santa Avelina, in Quiche, Guatemala with Teachers2Teachers International. William M. Botnan has 137 students total in the primary grades. There are sixty students in the pre-primary grades. There are two other schools that are pre-primary/primary in Santa Avelina. There is one other that is just pre-primary. The primarily language in Santa Avelina is Ixil (ee—sheel), a Mayan language. Most people learn Spanish by the time they reach first grade. A few people can speak a little English.

In this report, I describe my visit Willam M. Botnan School in Aldea Santa Avelina, in Quiche, Guatemala with Teachers2Teachers International. William M. Botnan has 137 students total in the primary grades. There are sixty students in the pre-primary grades. There are two other schools that are pre-primary/primary in Santa Avelina. There is one other that is just pre-primary. The primarily language in Santa Avelina is Ixil (ee—sheel), a Mayan language. Most people learn Spanish by the time they reach first grade. A few people can speak a little English.

February 6, 2017

Morning

The team in Santa Avelina made some

advance decisions over dinner in

Chichicastenango that were helpful in

constructing an organized and efficient

workshop. The workshop provided

professional development to help teachers

plan lessons that foreground students’

mathematical and scientific reasoning. The

morning sessions were organized around the

metaphor of a coin, where one side of the coin

represents “students thinking and talking” and

the other emphasizes “the teacher listening to

the students’ thinking”. Arthur set the tone for the day by introducing the metaphor.

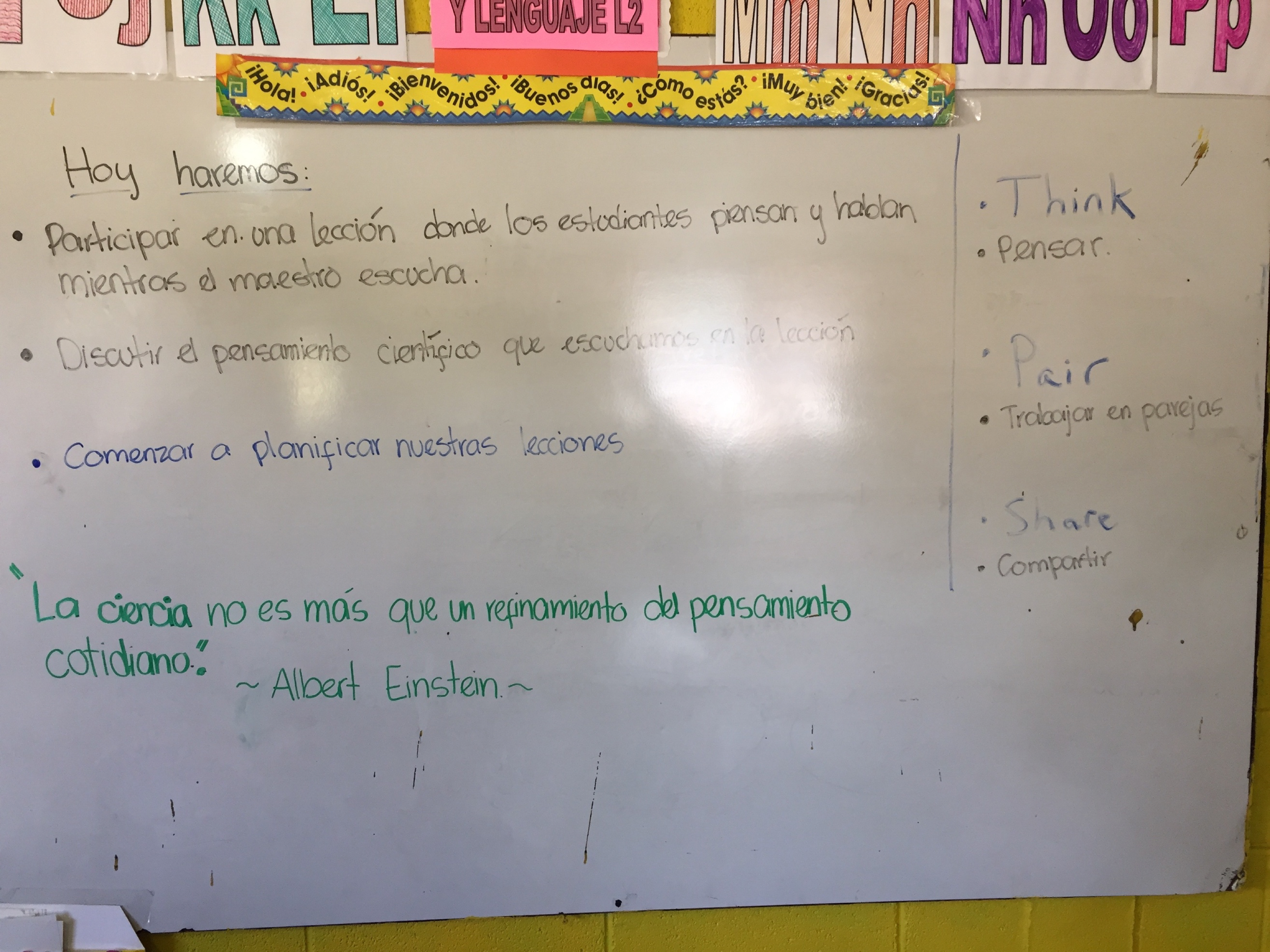

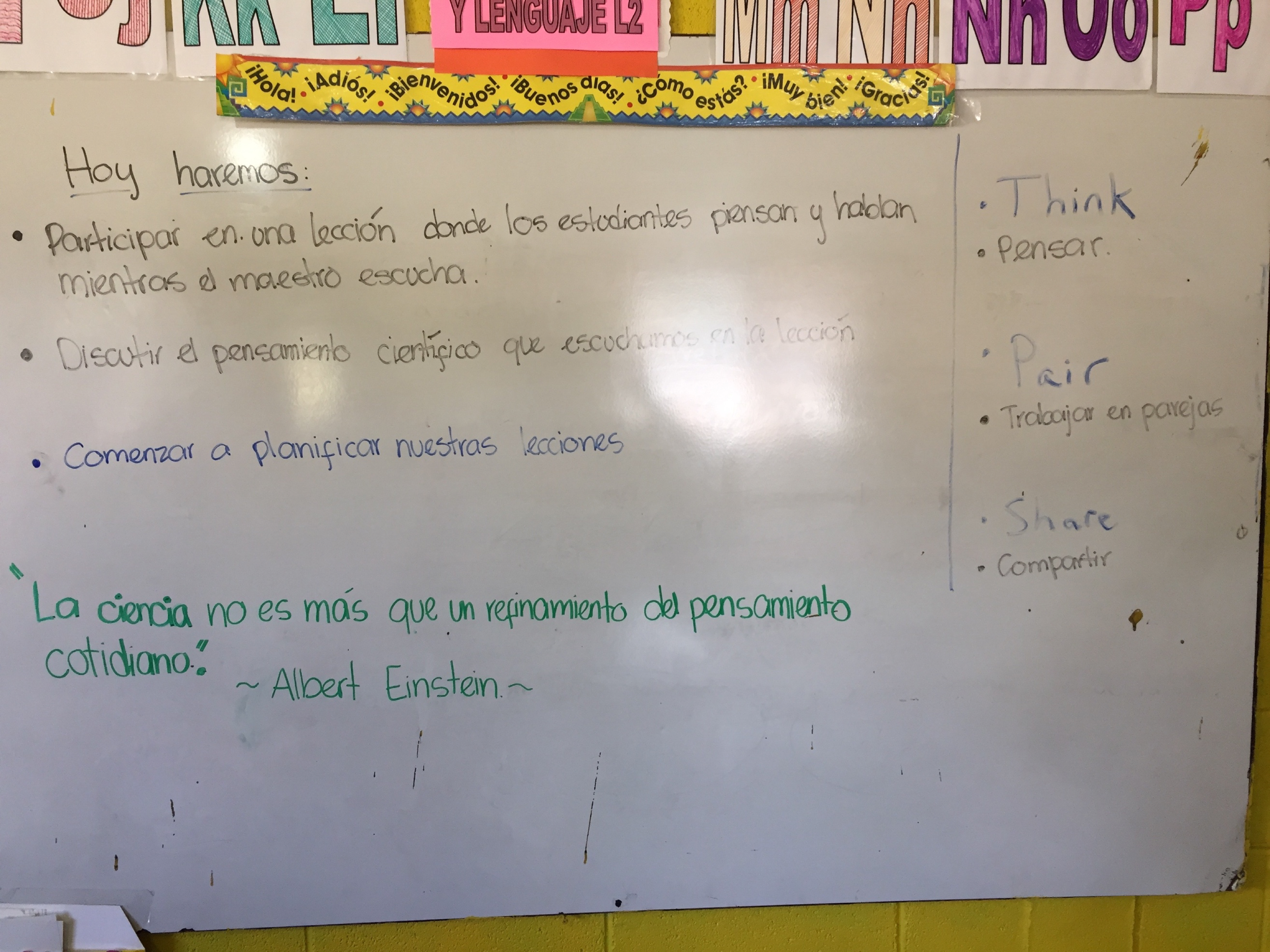

The teachers were split into two groups, upper elementary and lower elementary teachers. Becky and I took the upper elementary group for the first session, with Carmen interpreting. Arthur and Hans took the other group and then we switched. The overall outline for our part of the morning session was written on the white board:

Today we will:

Participate in a [model] lesson where the

students think and speak while the teacher

listens [and responds].

Participate in a [model] lesson where the

students think and speak while the teacher

listens [and responds].- Discuss the thinking that we heard in the lesson.

- Begin planning our lessons.

The primary goal was to model a science lesson that

emphasized students’ exploration of a scientific question before the teacher (or ideally, the students) explained the correct answer. We emphasized this approach of “exploration proceeding explanation” throughout the morning and afternoon sessions and routinely connected it to the “two-sides-of-a-coin” metaphor. Students reason (explore and explain) while the teacher listens and guides them if and when necessary. Secondary goals included introducing the Think-Pair-Share strategy, which can create equitable opportunities in a whole-class discussion, and introducing two planning tools: The 5E’s Lesson Plan template (Bybee et al., 2006) and a “Backwards Design” tool (Wiggins &

McTigue, 2005). The 5E’s is a science lesson-planning model that emphasizes “exploration proceeding explanation,” while the Backwards Design tool we created is a more general tool that is useful for aligning objectives, activities, and assessment.

The science question for the model lesson needed to be difficult enough to challenge the teachers as they took on the role of the student—as such it did not directly connect to their curriculum. It is worth reconsidering this for the future. It may be possible to accomplish the same ends while modeling a lesson that teachers could realistically use in their classrooms. It would be useful to have information about the teachers’ curriculum prior to planning the sessions and having materials translated.

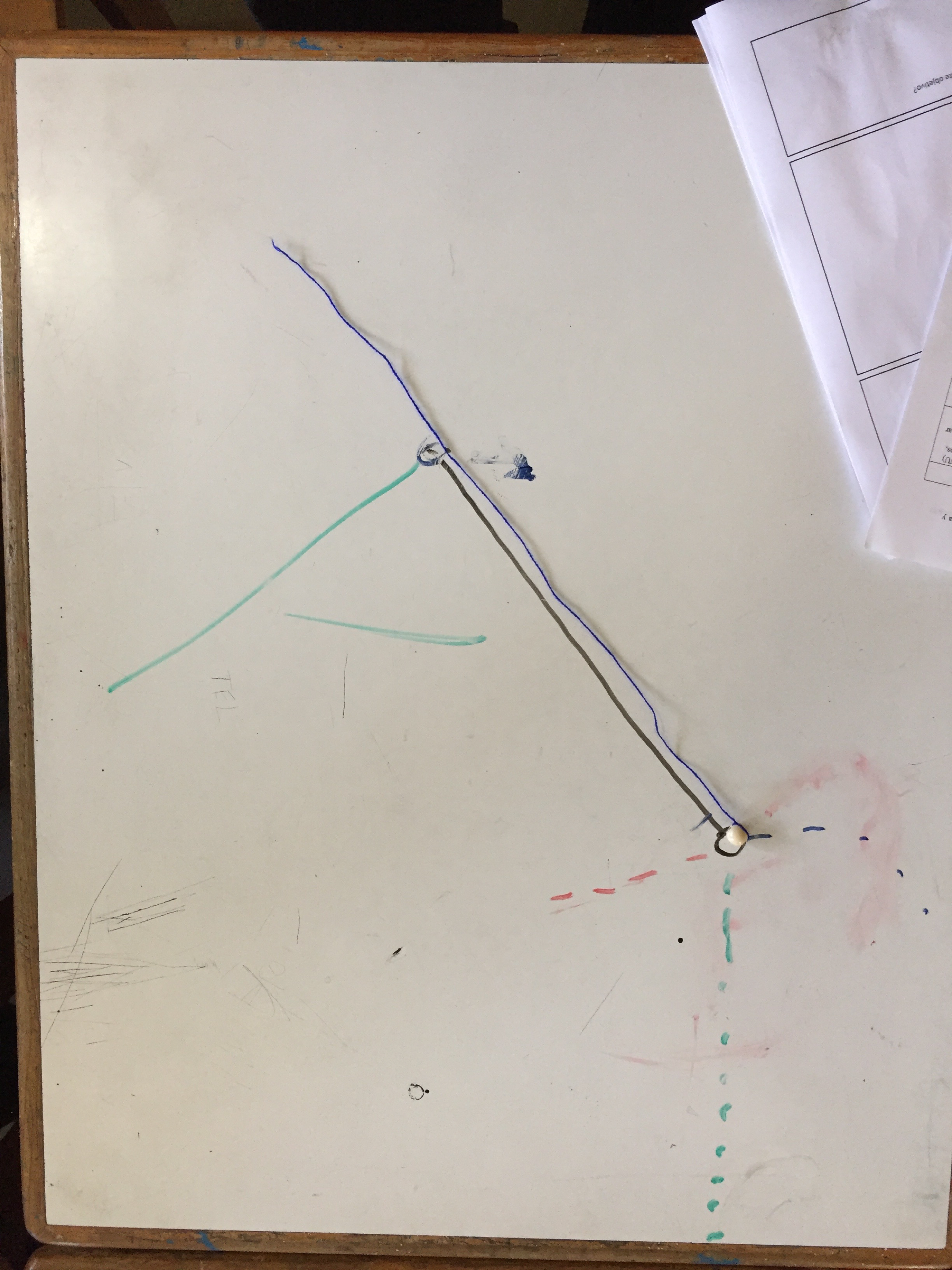

We used a question developed by a middle school teacher and described and published as part of a collection of case studies of elementary students’ scientific inquiry (Hammer & van Zee, 2006). I swung a bead on the end of a piece of string (I bought the materials in Chichicastenango). and asked, “If I were to swing this bead back-and-forth like this, and cut it when it reaches its highest point, just when it is about to come back down, what will happen to the bead?”

In our early team discussion about Santa Avelina, I had been told to expect a very reserved, polite group who would sit down and talk quietly. My personal style is to move about the room, usually bubbling with enthusiasm. In most cases I can’t help myself, because I get excited. But in this case, I was restrained, and we sat together at a set of desks discussing the pendulum question. (A nice feature of William N. Botnan is that the desks are all whiteboards.)

In our early team discussion about Santa Avelina, I had been told to expect a very reserved, polite group who would sit down and talk quietly. My personal style is to move about the room, usually bubbling with enthusiasm. In most cases I can’t help myself, because I get excited. But in this case, I was restrained, and we sat together at a set of desks discussing the pendulum question. (A nice feature of William N. Botnan is that the desks are all whiteboards.)

People were certainly very polite, but not

particularly more reserved then most teachers I have worked with in this kind of setting. We did a quick think-pair-share to get them started and to model the approach, and the ideas began flowing rapidly. Maria suggested that since the bead was at its “highest point”, and “about to head back in the other direction”, it would fly back in the direction it came from on an angle (the red dashed line on the diagram). I asked people about Maria’s idea. I reminded the teachers that in science, we make progress by disagreeing with ideas, and arguing for or against explanations and predictions. In everyday life, I said, we  might think of arguing as negative. We don’t really enjoy

hearing two brothers arguing over who has to do a chore, for

example. But arguing in science has a purpose of bringing us to

greater understanding.

might think of arguing as negative. We don’t really enjoy

hearing two brothers arguing over who has to do a chore, for

example. But arguing in science has a purpose of bringing us to

greater understanding.

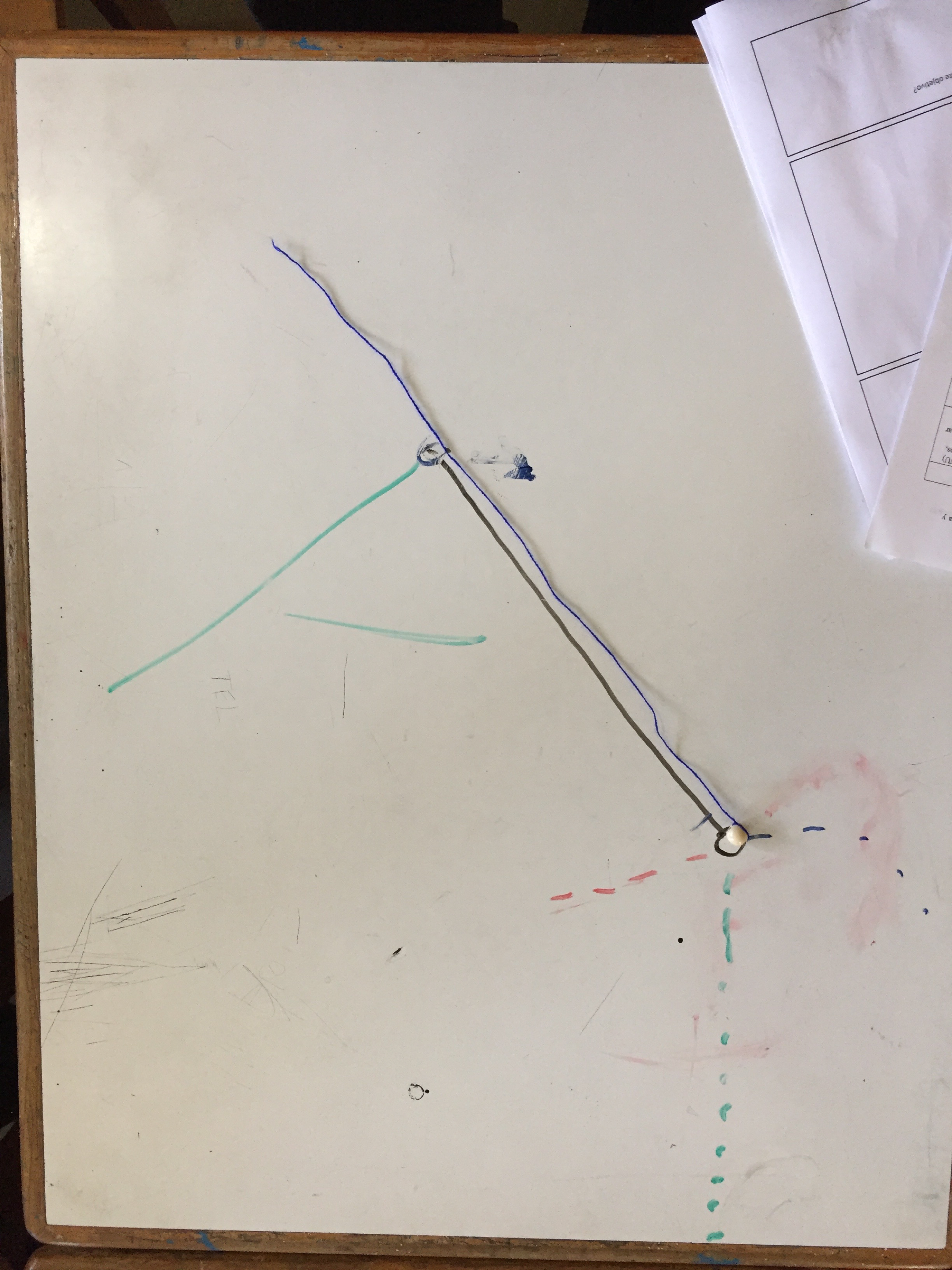

On the diagram to the right you can see the developing predictions. You can see the string and bead stretched out along the brown/black line. Domingo disagreed with Maria. The bead has it’s own strength (force) and momentum, he asserted, and so it would fly off in the direction it was heading (the black dashed line). Juan, the computer teacher, disagreed with both of them. He drew the green line to show that the bead was moving in both directions. He then pointed out that just went the bead was ready to come back down it did not have any force acting on it except gravity, and so it would fall straight down. The discussion and argument proceeded in much the same way it does when I do this with pre-service and in-service teachers in the states, and in my experience in other countries. The teachers readily drew on their experience of being on a swing. They questioned exactly when the string is cut, and as usual, there was discussion about how ideal conditions are presumed in physics. We discussed the ways in which the idealization of physics has to be reconciled with phenomena in the natural world, which occur under the influence of complicating variables. From there, I gave each pair of students a bead on a string, to “try out” different ideas they had and come up with revised explanations. I even told them I had more beads and more string if they wanted to try other things. Ultimately, we came back together and discussed our newest ideas.

I’ll pause in my description of the workshop here to explain a little more about why I ask science questions in professional development with teachers. First, I want to model for teachers how they can engage students in interesting scientific questions, create opportunities for students to reason scientifically, and move, through instruction that foregrounds students’ ideas, toward students’ deep understanding of central concepts in science. In this case, the central concepts are conceptual (i.e., force, momentum, speed), epistemological (scientific prediction involves reconciling personal experience with physical laws), and practical (students must propose and argue for and against predictions). Second…it’s fun. It reminds us that science is about exploration, discovery, excitement, and understanding. It’s PE (physical education) for the mind. Finally, if we expect science teachers to push their students to reason, we must provide them opportunities to push themselves. This helps them not only to understand how their students might respond to instruction that promotes scientific reasoning but also to identify and empathize with the feelings of pursuing an explanation for a phenomenon for which you do not know the answer.

As usual, I did not volunteer the “correct” answer. And as usual, at the end of our investigation, someone asked me for the “correct” answer. I’ve worked very hard at answering this question. My first response is that a physicist would say that under these idealized condition, when the bead is just about to come back down, it has no velocity and no momentum, and the only force acting on it is gravity. Thus, Juan represents the physicists, who would say that the bead would drop straight down. I demonstrate what one of my former students once showed me. If you imagine that the bead is swinging very slightly, the “highest point” is one in which the bead is moving quite slowly. You could, then, consider the bead to not be swinging at all. In this case, the “highest point” is when it is still…suspended from the hand and pointed toward the floor. At this “highest point”, where will the bead go?

In a class with students, I might not reveal the correct answer. If were continuing to work on this problem, I might send them home to think about it, or give them a writing

assignment. In workshops with teachers, however, I don’t want to frustrate them, as we might not get a chance to return to the question. I carefully explained that in this case, physicists would argue that Juan was correct. At its “highest point” the bead has no momentum, no velocity, and would fall straight down under the influence of gravity. I always feel a certain satisfaction when people ask for the right answer. To me it means that I let them reason, as I want them to let their students. I did not just tell them, with authority, what they should think. I also raised the question of what the right answer is. Is the right answer what would happen to the bead? Or is the right answer that students can apply concepts of force, momentum, velocity, and gravity in their pursuit of an explanation. And when is the right answer important? Do students have to know the right answer at the end of class? Or could they have time to reconsider it, review the arguments, try out new things, and question their own understanding?

I do like it when people ask the “right answer” question. It gratifies me that I have not pushed them towards it, because that is not my goal. And I’m not convinced that the right answer (in this case, what happens to the bead…) really is important for science learning.

It’s important not to disregard the gender dynamics in Santa Avelina. Domingo and Juan led the conversation, with contributions from Juan Castro and Maria. However, it was clear that Domingo was “the one who knows”, and so it was a learning experience for all of us that Domingo’s response did not match with the canon of physical kinematics. Domingo did not seem upset. He strikes me as a person of great curiosity, who is not afraid to be wrong.

The “bead-on-a-string” conversation was quite productive with this group, and I always have to force myself not to artificially cut off productive work. Once we had discussed the “physicists’ answer”, I introduced the NGSS (2013) scientific and engineering practices, and we discussed which of these we had pursued in the “bead-on-a-string”. We were able to check off most of them.

Science and Engineering Practices (Inquiry)

(US Next Generation Science Standards)

- Asking questions (for science) and defining problems (for engineering)

- Developing and using models

- Planning and carrying out investigations

- Analyzing and interpreting data

- Using mathematics and computational thinking

- Constructing explanations (for science) and designing solutions (for engineering)

- Engaging in argument from evidence

- Obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information

Finally, we introduced the tools that we thought the teachers might use in planning science lessons. We introduced Bybee et al.’s (2006) “5E’s”, which the El Paredon teachers had helped us modify2. I had prepared a 5E’s outline of the lesson I had intended to use with the teachers, (which for the upper elementary teachers was “The Owls and Snakes problem”—Levin, Hammer, Elby, & Coffey, 2012). I emphasized that

Lesson Plan (Middle School)

Objective: Students will make hypotheses about a biological relationship and analyze data to come to conclusions. “The ‘5E’s’ Lesson Planning Model”. The 5E’s is not a “Magic Lesson Plan Format”. It might not apply to all lessons, and we should not treat it as a linear guide. Evaluation (assessment), for example, is something that should be ongoing, responsive, and formative in that students’ thinking feeds back into what the teacher decides to do. The intention of the 5E’s–its spirit–is that the teacher considers the opportunities for students to reason (the flip side of the coin) before the phenomenon is explained (the head of the coin). In theory, it is the students who explain the phenomenon. In practice, the teacher often participates in the explanation. This seems fair and pragmatic in a school system context. There are some things that the teacher must authoritatively tell the students if they expect they will be judged on the students’ understanding of the canon. Additionally, we shouldn’t necessarily expect that students “discover” all knowledge on their own, when the history of science tells us that scientific knowledge and theory have been developed and refined over time. Aristotle knew less about the variety of chemical elements than today’s eighth grade student in Santa Avelina does.

The 5E’s, while not a “Magic Lesson Plan Format,” is a useful structure within which a teacher could construct a good science lesson plan. For the Santa Avelina teachers, we wanted to emphasize that students should be doing the reasoning, and teachers should help them use their reasoning to understand scientific knowledge and practice. I often recall the first lesson that one of my pre-service teacher students demonstrated in our first science methods class. “Mary” had a background in archaeology and earth/space

In the discussion afterward, I suggested to Mary that she could “flip it”. Why couldn’t the students explore the soil characteristics before they were told what the soil types were? My knowledge of the literature on constructivist learning theory, and my experience as a learner, teacher, and parent convince me that experiences anchor students’ science learning. “Exploring before explaining” is a pedagogical implication of constructivist learning theory.

Back in Santa Avelina, with about 15 minutes left in our time, we introduced the Backwards Design Tool We also gave the teachers a blank version of the 5E’s. We had hoped to give them planning time in the morning, but it was clear that they would need more time in the afternoon.

Soon it was time to switch and work with

the lower elementary teachers. Rather than

describe again in detail how this same

approach worked with the lower elementary

teachers, I’ll summarize. The lower

elementary teachers, predictably, were not as

comfortable with the science as the upper

elementary teachers, and struggled a little

more to come to a sensible consensus

response to the bead on the string question.

They did, however, participate as readily as

the first group in listening and responding to

each other’s ideas, identifying scientific practices, and beginning to work with the lesson planning tools. I gave them another model 5E’s lesson plan—in this case focused around the question, “If I drop this book and this piece of paper at the same time, which will fall first and why?” (see Hammer & van Zee, 2006)4. We had a little more time with these because the arguments about the bead on the string did not go on long, but still we knew we needed more time to work with this group on lesson planning.

Afternoon

Becky and I briefly discussed the

afternoon plan over lunch. We met with

both groups and concentrated on helping

them plan a lesson using the Backwards

Design tool. Becky came up with some

clever ideas: She had Carmen write out

our afternoon “lesson plan” in the format

of the tool we wanted the teachers to fill

out. She also came up with a list, which

identified important questions someone

could ask about each of the parts of the

lesson plan. We introduced the agenda to

the teachers and gave them around twenty

minutes to work on it, either alone or in pairs. We then went around to the circle and each teachers described their lesson plan. We gave feedback and asked them to give each other feedback, using the list of questions to guide what they asked. I won’t go into too much detail on each conversation, because a lot of what we discussed comes out in the classroom observations and my analysis; I was very surprised and excited to hear that each teacher planned to teach the lesson they constructed in class the next day.

February 7, 2017 Classroom observations and post-observation discussion with teachers

Grade 2:

Juana Priscilla

Today, I visited five classes. First, I visited Juana Priscilla’s 2nd grade class. There were 20 students: 9 boys and 11 girls. When I arrived, the students were still working on a language lesson. The class was organizing words on the board in alphabetical order. Juana Priscilla asked students to come up to the board to determine where the words fit, and then asked other students if they agreed or not with each other’s choices. She also asked students to explain why they placed words in the order they did. For example, she asked students, “Which comes first, ‘libra’ or ‘lapiz’.” When one boy said “lapis” she asked him to explain why. He said “lapis” comes first “because of the a.”

After about 15 minutes, Juana Priscilla told the students that they next day they would be doing the same thing, but with their own names. Then she had everyone get up and stretch, to take a break, after which she said that they were going to switch to science.

Here is the lesson plan that Juana Priscilla wrote in the workshop the day before. In discussion, it became clear that she wanted students to know the parts of the human body; specifically, she wanted to begin talking about the skeletal system.

To begin, she asked the students if they remembered what they had done in last week’s science lesson, and they replied that they had talked about the parts of the human body. She played a quick game where she touched different parts of the body and asked students to say what they were. The students were very responsive to Juana Priscilla and there was a lot of smiling and friendly rapport.

Next, Juana Priscilla used the analogy of building a house to

introduce students to the skeletal system. She told them that

her father wanted to build a house. What materials did he need? Students mentioned concrete, wood, and steel. One boy, apparently anticipating the analogy, said that the steel was like the bones of our body. Juana Priscilla asked if other students agreed with his idea and most students nodded or said they agreed. Juana Priscilla asked why the house needed steel, and the same boy said that the steel helps to hold the house up, like our bones do for our body. For me, this was one of the most important moments of the visit. Juana Priscilla had taken seriously our idea of having students do the reasoning while the teacher listens (the two-sides-of-the-coin). By doing so, she had seen first-hand how a student’s idea can drive the lesson. This is the essence of “responsive science teaching” (Robertson, Scherr, & Hammer, 2016), where students’ scientific ideas are foregrounded and may even serve to drive the direction of the class.

As much as any teacher we saw, Juana Priscilla directly put the ideas of the previous day’s workshop into practice. Right before I had to leave to go to the next class, she transitioned the class to begin talking about the different bones in the body. She put the students in pairs and asked them to discuss which of the bones in our body are long and which are short. We had to go, but it was clear that she was using the Think-Pair-Share strategy that we had taught the previous day. It will be interesting to follow-up with Juana Priscilla in particular, to see if her appropriation of these new pedagogies is sustained after we are gone.

Juana Priscilla introduced a minor content error in the lesson. The error is so minor, and might seem so insignificant, that it is hardly worth mentioning. However, the introduction of minor content errors, delivered with the teachers’ authority, was a fairly consistent theme throughout the day. I will document each one and note why I think it is important. In this case, in one point of the lesson, Juana Priscilla asked the students “Do all animals have bones?” The students replied that yes, all animals have bones, and Juana Priscilla affirmed their response. In fact, only a small fraction of animals on earth have bones. I mentioned this because one of the reasons that we define things in science is so that we can establish precision in communicating with one another. An animal is any organism that is composed of multiple cells and consumes other organisms for food. Therefore things we might not consider animals colloquially, such as worms or insects, do qualify as animals in a system of scientific classification. This in not an uncommon mistake among elementary teachers, but I consider it an important point; if children are to learn about animals, teachers should understand and use the classification scheme that scientists use. This not only gives students the “correct” answer, but it helps to establish the importance of terminology as a tool for communicating effectively and with precision.

My observations guided my conversations with the teachers in our afternoon sessions. I shared with Juana Priscilla’s my positive assessment of her pedagogical approach and the classroom climate, and I drew her attention to the minor content error.

Grade 4: Maria

Next, I visited Maria’s 4th grade class. There were 20 students, 10 boys and 10 girls. I arrived just when the class was switching to science. Maria told the students that they were going to talk about the bones in their face. Like Juana Priscilla, Maria used the lesson that she had designed the day before in the workshop. In fact, all five teachers I

observed used the lesson they designed. All of the lessons incorporated the idea of “explore-before- explain,” but as I will explain, some did so more effectively than others.

It was initially unclear to me what Maria meant by “the bones in the face”, and as it turned out, she meant the teeth. This is another content error. Bones and teeth differ in both structure and function. In our conference afterwards, I initially decided not to bring this up with Maria. The entire group was meeting together, and I didn’t want to embarrass her. However, after I gave her my feedback, she asked me if there was anything else I thought she could do better. I brought up the confusion of bones and teeth, and as it turned out, most

of the other people in the group also thought that bones were teeth. My confidence wavered, and we looked it up. As I expected, bones and teeth differ in both structure and function. Again, this may seem like a minor point, but understanding the relation between structure and function is an important aspect of science that cuts across scientific disciplines such as biology and physics (NRC, 2013). Thus discussing the differences between bones and teeth, rather than simply treating them as the same, could be a productive way for students to understand and appreciate this important relationship.

Maria made efforts to tap students’ prior knowledge, and as a result, it was clear that students knew quite a bit about teeth. She asked them about when they got their first teeth, when they lost their “milk” teeth, and what would happen if they did not have teeth. She explained why they were called milk teeth5, and emphasized the importance of dental hygiene. She had students count their teeth. Most found that they had 28 teeth, and Maria explained that most adults have 32.

I found it particularly interesting when Maria asked the students why the “pre-molars” are called pre-molars. I was very excited about this at the time; I thought that she was attempting to integrate some literacy into the students’ understanding of the names of the teeth. That is, if the students understood that the pre-molars are teeth that come in before the molars, they would have an example of how the prefix “pre” is used. Understanding this prefix could be useful to them in their developing Spanish language proficiency. When I asked Maria in the conference afterwards why she had asked that question, however, she responded that she wanted the students to know the names of the teeth. Either she didn’t understand my question, or she was not really trying to integrate understanding of the prefix. I believe it’s the former. During this discussion Maria did not ask the students why the incisors are called the incisors nor why the molars are called molars. I think she recognized the value of drawing their attention to the prefix.

After this discussion, Maria had the students open the book, copy the picture of the mouth in the book, and label the teeth by their names. I was unimpressed with this activity. I realize that it is part of the curriculum, and Maria has very little training or support to think about how to do something differently. However, the activity used a large amount of instructional time that could have been spent more productively. For example, Maria could have had students look at pictures of bones and teeth and compare and contrast their structures and functions, perhaps with a Venn Diagram. This approach would not only draw students’ attention to the structure/function relationship, but would give them an opportunity to identify the particular structures of both tissues.

Grade 1: Magdalena

After a break, I visited Magdalena’s 1st grade class. There were 20 students: 11 boys and 9 girls. This was a very active, very noisy class, but it was warm and friendly and the children were on task. Everyone was smiling and laughing throughout the lesson, and Magdalena is warm and encouraging with the students. The lesson was about the parts of the body, and Magdalena first had all the students stand up to sing a song that they had learned about “Aunt Monica”.

I didn’t ask Carmen to translate the song entirely, but it basically has lines like, “My Aunt Monica, she has shoulders, and when she turns around she goes like this”…(and everyone shimmies their shoulders). Magdalena began the song and in the beginning, she took the lead with the singing. Over time, however, she would stop singing to let the students take the lead. (I have video evidence of this). This “fading” of support helped students to independently identify the body parts without Magdalena’s support.

After the song, Magdalena asked the students a few questions to extend their understanding of the body parts and their Spanish terms. She asked, for example, “Why are they called “ears” and not “ear”? One student said, “because they’re big” and another said, “because there are two of them.”

I found Magdalena to be the most pedagogically sophisticated of all the teachers I observed, although Juana Priscilla and Domingo were both also very strong. For the next activity, Magdalena gave the students cutouts of pieces of a drawing of a boy and told them they needed to put the pieces together to make the picture of the boy. She also gave them labels with the Spanish terms for the body parts, which they were expected to glue on next to each body part. The students were in groups of about five. Magdalena had cut out the pieces, but only very roughly. She handed out scissors and had the students cut out the pieces carefully around the outlines of each shape.

My first thought was that this was a waste of instructional time. I thought she could have made better use of the time if she had cut the pieces out completely before hand. I decided, however, that since this was a first grade class, Magdalena probably wanted to give the students practice in using the scissors. Young children often have difficulty with fine motor skills, and this seemed like a good choice to help them develop these skills. It turned out, however, that Magdalena was making a much more sophisticated pedagogical choice. Carmen pointed out to me that while the children were cutting, Magdalena went around to each child individually, held up the names of the body parts and asked the child to say the word and identify the part on their own body. Thus she managed to engage the whole class actively in group work while creating time for her to work one-on-one with each student. I was very impressed; I would consider this sophisticated pedagogical decision making if I saw it in the States.

I was already very impressed with Magdalena’s class

when Carmen interpreted a conversation Magdalena was

having with one boy. The boy came up to her and asked her what one of the terms meant. Instead of telling him, she directed him to ask one of his classmates. After Carmen pointed this out to me, I watched as the same boy came up to ask Magdalena about a different term. Again she told him to ask his classmates. She did the same when another student came up to her. After a while, no more students came up to ask her, and we could hear the students discussing among themselves which label went where. Magdalena was the one teacher I had difficulty offering critical constructive comments in the conference in the afternoon. Pedagogically, it was one of the most impressive primary classes I’ve ever seen. By the end of this class, I’m certain that Magdalena could tell me what progress each of her students had made in identifying the Spanish terms for the body parts.

Grade 6: Domingo

Next I visited Domingo’s 6th grade class. There were 17 students in the class, 8 boys and 9 girls. I was very excited to see this class for several reasons. First, my expertise is in science education in the middle and secondary grades, so I felt more comfortable observing a lesson at this level. Second, I know that Domingo had put a lot of effort into this lesson and was anxious for me to see it. In the planning session on the previous day he had asked me if I had ideas for how to go about teaching “The Scientific Method.” I don’t think I did a very good job helping him with this. I am personally uncomfortable with the reification of the particular series of steps taught in schools as “The” scientific method. In reality, scientific work follows a variety of methods, only some of which have the hypethetico-deductive character of the method that is traditionally taught in schools (Tang, Coffey, Elby, & Levin, 2009). I also felt a little put-on-the-spot to come up with something that Domingo could do with the materials he had available. I was asked the same question in El Paredon, and I think I

handled it poorly there. With Domingo, I launched into a

long response based on how Becky and I had responded in

El Paredon. First, I explained that the key to this particular

method was to have some sort of comparison, where the

variable that is being tested can be compared to a condition

in which the variable is absent (i.e., a “control” group).

(This is often referred to as the “Control of Variables”

strategy, or “CVS”). I then described how Domingo could

have students grow different groups of plants, and ask

questions about what factors affect plant growth. For

example, students could ask how the amount of water

influences plant growth. They could grow groups of plants

under different daily watering conditions (i.e., no water, .25L water, .5L water, etc.) and measure the growth of the plants. This kind of experiment is likely familiar to most readers of this report. It’s “The Scientific Method” taught in schools, and it is usually the kind of thing that people think of when they think of science fair projects. Despite my own discomfort with the dominance of this particular method in schools, I thought that my suggestion might help Domingo come up with some ideas, and I particularly wanted to emphasize the importance of the CVS strategy, so he wasn’t just teaching students a set of steps. I judged from the look on Domingo’s face that he was dubious about my suggestion. He and Juan (the computer teacher) huddled together during the planning time, and they came up with another plan that Domingo taught and that I recorded in its entirety.

Domingo began the class explaining to the students that we all have questions, and that questions are important in science. He asked the students what kinds of questions they had. I was so engrossed in video recording that I didn’t take very good notes in this class, but it was clear that Domingo valued his students’ ideas and was taking all questions, even if some of them did not sound like science questions. His intention, which he had told me the previous day, was to let students explore a particular phenomenon and then demonstrate to them how their exploration fit into the steps of the scientific method that he ultimately wanted them to know. As the class went through each part, he recorded it on the white board.

Domingo then told the students that he had a question he wanted the class to explore. He asked the students what they thought would happen if he placed an egg in “sweet” water (emphasizing that by “sweet” he did not mean that it had sugar added, but merely that it was pure, with nothing added). Students came up with several ideas. Some said it would sink, and some said it would float. One boy said that he thought the egg would explode. Rather than dismiss the idea as ridiculous, or ignore it, Domingo, said, “Okay” and wrote the idea down with the others. He told the class that everyone had different ideas and there were no wrong answers when you are saying what you think. Again, as with Juana Priscilla, this was a sophisticated “responsive” pedagogical move. First, perhaps the boy was joking, and trying to draw attention to himself by saying something ridiculous to get a laugh. By taking the idea seriously, Domingo diffused any possibility that the boy would benefit from negative attention and thereby disrupt the class. Second, it’s possible that the boy really thought this was a plausible idea; Domingo didn’t really know if the boy was serious or joking. (He said it with a perfectly straight face). Ultimately, Domingo’s acceptance of the idea demonstrated that his classroom was one in which students’ ideas were valued.

Domingo then asked students what they thought would happen if he placed the egg in salt water. Students offered similar responses. Some said it would float and some said it would sink. Again, someone came up with an unusual idea (although I can’t remember exactly what it is—you’ll have to watch the video), and again Domingo accepted it as plausible. With this list of what the students thought would happen in salt water and sweet water, Domingo told the students that what they had come up with were referred to as “hypotheses”.

It was time to see what happened. First Domingo placed the egg in sweet water asked the students what they observed. The students noted that the egg sank. He returned to the board and crossed out the hypotheses that could be eliminated: the egg did not float, and it did not explode. In doing so, Domingo made a visual statement about the nature of science that distinguishes it from mathematics: In science, we make progress not by “proving” certain things to be true, but by showing that alternative possibilities are untrue. He didn’t discuss this with the students, but I mentioned to him in the post-observation conference that this was a powerful display of the nature of science.

Next Domingo began to add salt to the water, stirring it slowly as he did so. The egg continued to remain at the bottom of the beaker, and I got a little nervous for him. He kept adding salt and continued to stir it, but the egg remained firmly at the bottom of the beaker. (I think he could have used a little less water in his beaker so that the salt concentration would have increased more quickly). I thought about asking him if he wanted me to go get more salt, and I was getting more and more anxious. Domingo stayed very calm, however, continuing to ask the students what they saw. “Is it floating now?” No, they said, it was not floating. He sent a boy off to get more salt, and continued to add salt when the boy returned with it. Soon, the egg floated to the top of the beaker. Again, Domingo returned to the board and asked the students which hypotheses they could eliminate. Together, the class crossed out everything except for the hypothesis that said that the egg would float in salt water. From there, Domingo wrote “conclusions” on the board and told the class that what they had found out about the egg (that it floats in salt water and sinks in salt water) were their conclusions. He asked the students why they thought this had happened. One student said it was because of gravity. There were some other ideas, but again, my notes were limited so I am mostly relating what I remember. Domingo then explained to students that this comparison demonstrated the concept of density. Because the egg was more dense than the sweet water, it floated. Because it was less dense then salt water, it floated. Above where he had written “conclusions”, Domingo wrote “analysis” and recorded the density explanation in that space.

I was very impressed with this lesson, although I had some constructive feedback for Domingo. Like the other teachers in Santa Avelina, Domingo has an easy, friendly, warm presence in the classroom. Students obviously feel comfortable sharing their ideas, and he is thoughtful about how he responds. This demonstration of the scientific method did not follow the typical control-of-variables strategy, although the comparison between salt and sweet water did allow for a comparison that could lead to conclusions. Frankly, I like what Domingo did better than what I had suggested to him. I certainly like it better than the typical “science fair” type of approach.

As with some of the other teachers, there were a couple of minor content errors. First, Domingo presented a conclusion as what happened. This is usually what we refer to as the “results”, “data”, “or findings”. A conclusion is the explanation itself. In our conclusion we explain why our results turned out the way that they did. Domingo did have the students discuss why they thought this happened, and he referred to this as the “analysis,” but I would like to see him accurately represent the explanatory nature of a conclusion. Domingo and I had discussed this when he planned his lesson, and I brought it to his attention again in the post-observation conference.

Looking back now, there are a couple of other things I should have mentioned in our discussion. First, there is a tendency to treat a hypothesis simply as a prediction, i.e., what will happen? In reality, a hypothesis is a proposed explanation. When someone offers a hypothesis, they don’t only say what they think will happen, but they say why they think it will happen. That is, they justify their prediction. What Domingo had students do was really just predict what would happen. I should mention that both the treatment of a hypothesis as merely a prediction, and the treatment of a conclusion as merely results are common errors among both middle and high school teachers in the States (as I pointed out with Juana Priscilla’s error about animals). Thus, I’m not identifying the Santa Avelina teachers as having any greater content weaknesses than teachers in the States. However, I think we should be ambitious and help these teachers to develop content expertise that is as strong as the best teachers in the States.

A second thing I should have mentioned in my conference with Domingo is that he could have had the students do the egg comparison, rather than doing it as a demonstration. Honestly, it seems obvious to me now, but I’m only thinking of it as I write this on the plane. He could have the students do it in pairs, and he could practice beforehand to make sure he told them what proportion of salt and water to use. I think it’s likely that Domingo either didn’t think of this or was nervous to try it. It complicates things considerably to have students do this themselves. A teacher has to consider that the results might not come out as expected for all the groups, and he would have to have enough experience with that to know what to do in that case.

Grade 5: Juan Castro

The final class I observed was Juan Castro’s 5th grade class. There were 18 students in the class, 7 boys and 11 girls. This was probably the weakest of the lessons I observed. The lesson was about the main parts of the cell, and Juan Castro read about the cell membrane, nucleus, and cytoplasm out of the book. After he read each section, he then had the students read each section. All the students read at the same time, at different rates, and the effect was just a loud babble of 18 voices reading asynchronously. I’m not convinced that it was a productive use of instructional time. From what I have heard, this is Juan Castro’s general approach to teaching.

After this, Juan Castro brought out an egg. He cracked the egg into a beaker and told the students that the egg was a model that represented a cell. Since the students had read about the three main parts, he asked them which part the various parts of the egg represented (i.e., the shell, yolk, and the amniotic fluid). Unfortunately, he provided no wait time, and did not let the students answer. Instead he asked the question as though it were rhetorical, and then quickly answered it himself. Thus, in contrast to some of the other teachers, Juan Castro did not foreground the students’ reasoning. I believe that what he took away from our training was that he should do some sort of demonstration with the students, which is how he assimilated our idea of “explore-before-explain”. He failed to let the students explore, however.

Teaching the parts of the cell in a meaningful way is not easy. I personally believe that is pointless to just have students look at pictures in the book and identify the structures. Who among us remembers the names of the cell structures that we learned in middle or high school? For me personally, these structures only became meaningful and important as I advanced in my study of biology. I believe, as I described in Maria’s class, that the study of the cell allows for an opportunity for students to appreciate the crucial relationship between structure and function. I published a short paper that describes how I approach teaching cell structure and function to make it more meaningful (Levin, 2010). Juan Castro did begin an effort to connect the cell structures to their functions, explaining to students, for example, that the nucleus contains the hereditary information. However, that does not really demonstrate the close relationship between structure and function. A better example is the cell membrane, in which the particular organization of the structure allows for the function of regulating what can enter and exit the cell.

Next, Juan Castro moved on to introducing the difference between plant and animal cells. Again, he read from the book, explaining to the students that the plant cell was square and the animal cell was round. He mentioned that there was one other difference, but did not say what it was. A girl asked him why the plant and animal cell was different. This is an excellent question, which gets at the nature of differences between animals and plants and emphasizes the structure/function relationship. Unfortunately, Juan Castro simply reiterated that they were different, i.e., the plant cell was square and the animal cell was round, and there was one other difference6.

I was becoming concerned about what I was going to say in my conference with Juan Castro. I wanted to make sure I could say something positive about each teacher’s lesson, and in this case it seemed that was going to be challenging. Juan Castro did something very productive at the end of the lesson, however. He returned to the egg demonstration, pointed to each part of the egg, and asked the students which part of the cell each part represented. This was a very useful assessment approach. Students were easily able to identify the analogy of the shell to the cell membrane and the yolk to the nucleus, but struggled to identify the analogy to the cytoplasm. Thus, at the end of the lesson, Juan Castro had a good assessment of what the students understood about the names of the different structures. It’s not clear why the students struggled more with the cytoplasm. It could be because it’s a more unusual term then the other two, or because it’s difficult to understand exactly what it is from the picture in the book. I’m not claiming that the students developed any real robust understanding of the cell from this lesson, only that pedagogically, Juan Castro appears to have appreciated the aspect of the Backward Design approach that calls for assessing students’ progress in meeting the lesson objective.

Post-observation Conference

After a wonderful lunch, we had about 45 minutes with each group to discuss our observations. I’ve indicated much of the specific feedback that I gave above. The teachers expressed gratitude for the feedback. Both Domingo and Juan Castro admitted to being very nervous. Both said that they were doing something they had never tried before. We joked that Santa Avelina should concentrate on doing “egg science”. Eggs are plentiful in Santa Avelina and they had already worked their way into two lessons. There are many opportunities to connect the local context in Santa Avelina to science lessons, but this was not a primary focus of this visit. In my next report, I’ll discuss how relating science to the local context became the primary focus in the El Paredon visit.

References

Bybee, R. W., Taylor, J. A., Gardner, A., Van Scotter, P., Powell, J. C., Westbrook, A., &

Landes, N. (2006). The BSCS 5E instructional model: Origins and effectiveness. Colorado Springs, Co: BSCS, 5, 88-98.

Hammer, D., & van Zee, E. (2006). Seeing the science in children’s thinking: Case studies of student inquiry in physical science. Heinemann Educational Books.

Levin, D.M. (2010). The invented cell: Supporting students’ reasoning about structure, function, and mechanism. The Science Teacher, 77(9), 64-65

Levin, D.M., Hammer, D., Elby, A., and Coffey, J. (2012). Becoming a responsive science teacher: Focusing on student thinking in secondary science. ArlingtonVA: NSTA Press

National Research Council. (2013). Next Generation Science Standards: For States, By States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press

Robertson, A.D., Scherr, R.E., and Hammer, D. (Eds) (2016) Responsive Teaching in Science. London: Routledge

Tang, X., Coffey, J., Elby, A., & Levin, D.M. (2009). Scientific inquiry and scientific method: Tensions in teaching and learning. Science Education 94(1): 29-47

Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. ASCD.

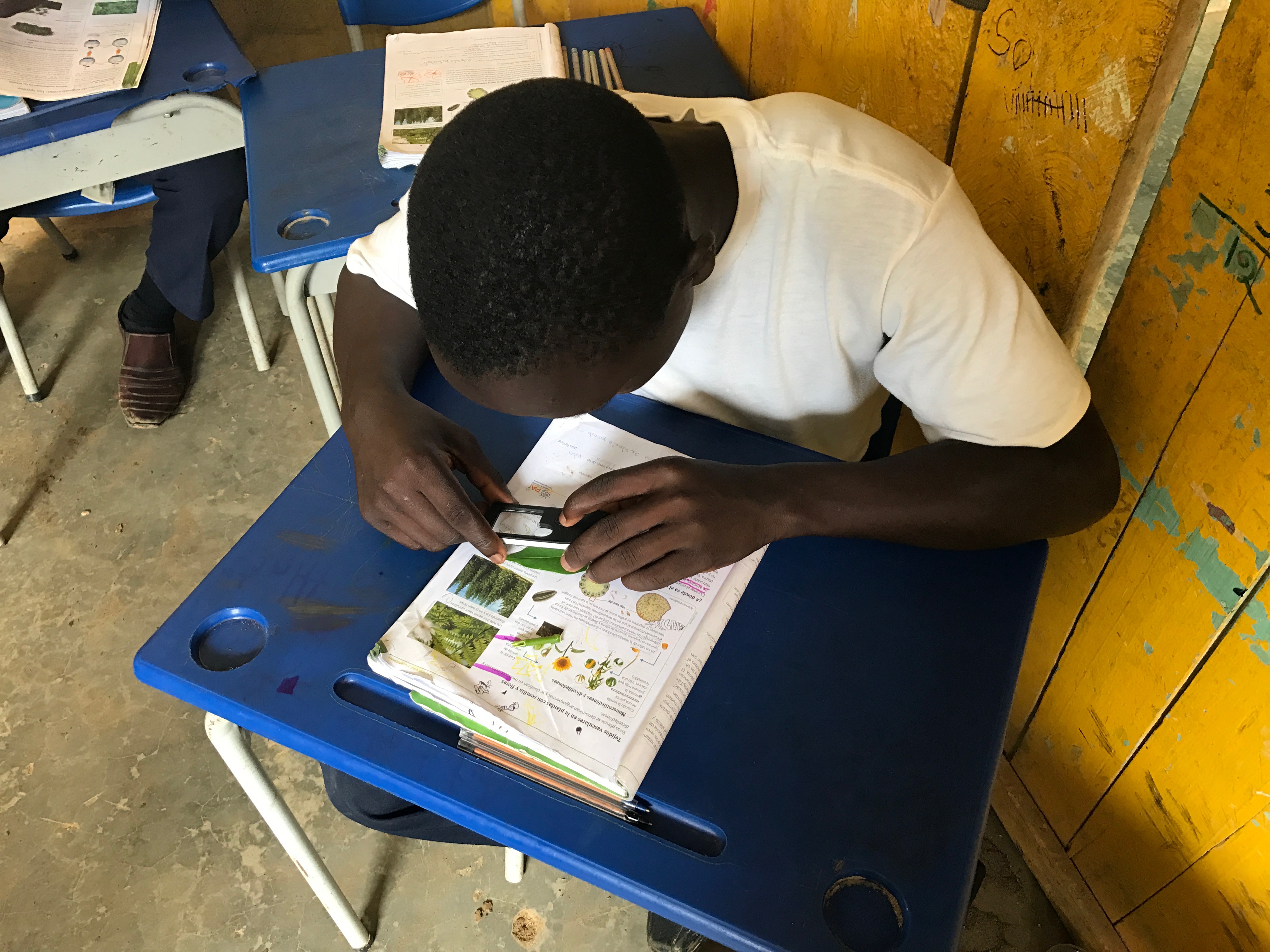

I continue to process my thoughts about my trip to Santo Domingo de Onzole on the banks of the Onzole River in Esmereldas Province, Ecuador. This story is about Robi and his middle school life science students, particularly a boy named Ariel, but it’s also about the microscopes I brought down and about questions about studying, learning, and science. Alex, as always, is involved.

I continue to process my thoughts about my trip to Santo Domingo de Onzole on the banks of the Onzole River in Esmereldas Province, Ecuador. This story is about Robi and his middle school life science students, particularly a boy named Ariel, but it’s also about the microscopes I brought down and about questions about studying, learning, and science. Alex, as always, is involved. Robi then went to the white board and drew a candle. “To Study is to the Wick as to Learn is to the Candle” he told them. The wick he, said, needed to be inflamed for the candle to work. Robi seemed to take this seriously. Shortly, the drum twanged and thumped again.

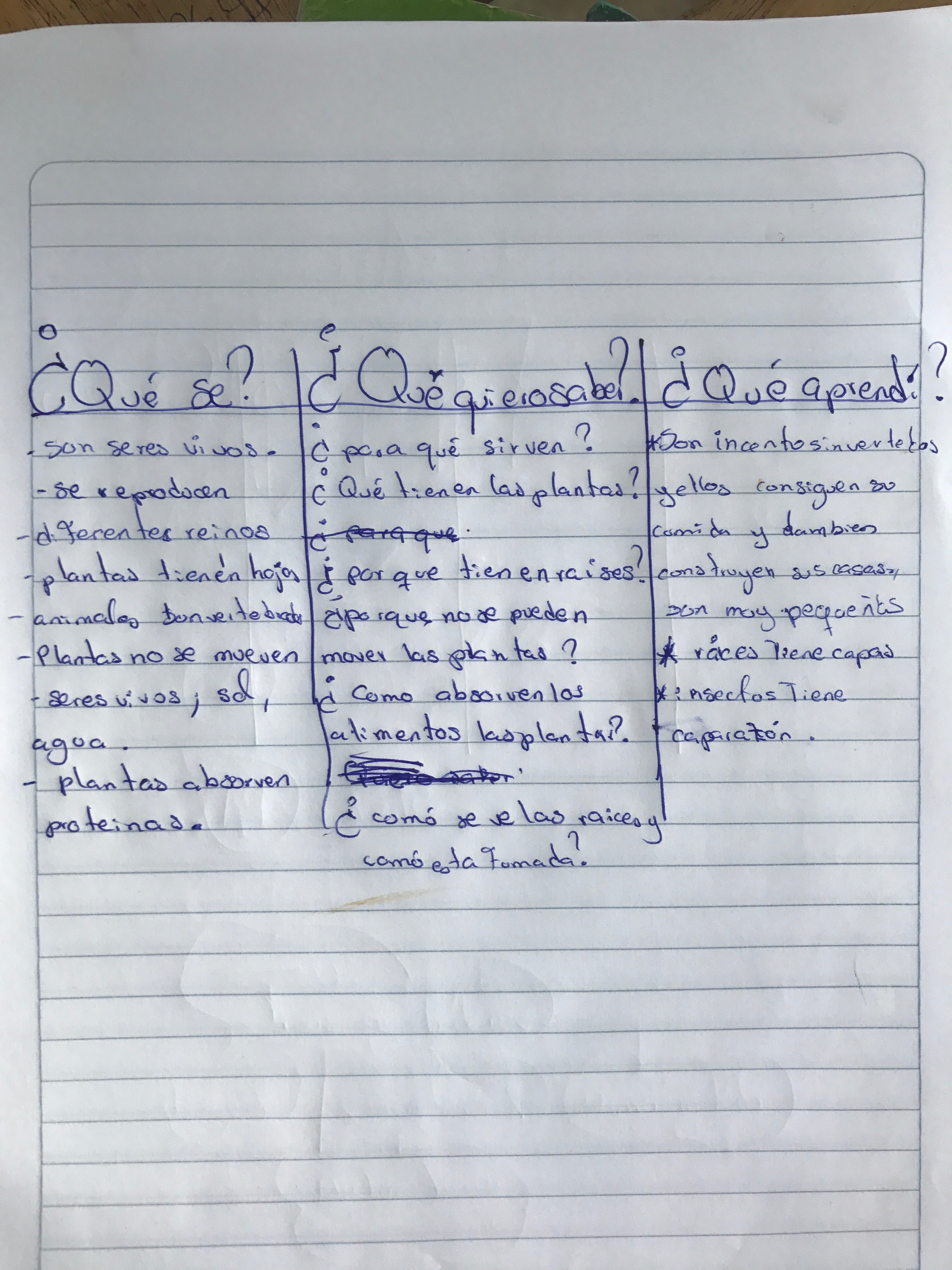

Robi then went to the white board and drew a candle. “To Study is to the Wick as to Learn is to the Candle” he told them. The wick he, said, needed to be inflamed for the candle to work. Robi seemed to take this seriously. Shortly, the drum twanged and thumped again. I wrote an objective on the board: “Students will be able to describe differences between plants and animals.” Again, Robi had not been at the PD sessions, so a part of this was modeling the idea that a clear objective was important and might be useful to communicate to the students, (as long as one doesn’t thwart students’ exploration by telling too much). Lucia and I led a whole class discussion about the “Know” column and students wrote down what the class generated. One example of a students’ paper can be seen on the right.

I wrote an objective on the board: “Students will be able to describe differences between plants and animals.” Again, Robi had not been at the PD sessions, so a part of this was modeling the idea that a clear objective was important and might be useful to communicate to the students, (as long as one doesn’t thwart students’ exploration by telling too much). Lucia and I led a whole class discussion about the “Know” column and students wrote down what the class generated. One example of a students’ paper can be seen on the right. Ariel arrived in Santo Domingo about a year and a half ago from a city in the south of Ecuador called Machala, not too far from the border with Peru. He had lived there all his life with his mother and his grand-mother after his father, originally from Santo Domingo, decided to leave and head back to the village.

Ariel arrived in Santo Domingo about a year and a half ago from a city in the south of Ecuador called Machala, not too far from the border with Peru. He had lived there all his life with his mother and his grand-mother after his father, originally from Santo Domingo, decided to leave and head back to the village. I can’t remember the wide ranging science conversation that resulted, but we looked closely at the wings and tried to watch its proboscis come out when we offered up a piece of papaya. I was astonished by Alex’s ingenuity in capturing and securing the butterfly. Alex loved science and math, but he especially loved biology. I felt a kinship. I imagine this is not uncommon for people working with Alex. He has an extraordinary ability to connect with people. Chadd, the director of T2T, had visited Santo Domingo before. When I mentioned Alex, Chadd remembered him well. “Wow! He must be a teenager by now!” Alex had been engaging outsiders for a while. Carlos said Alex was always at the guesthouse when Carlos was in town.

I can’t remember the wide ranging science conversation that resulted, but we looked closely at the wings and tried to watch its proboscis come out when we offered up a piece of papaya. I was astonished by Alex’s ingenuity in capturing and securing the butterfly. Alex loved science and math, but he especially loved biology. I felt a kinship. I imagine this is not uncommon for people working with Alex. He has an extraordinary ability to connect with people. Chadd, the director of T2T, had visited Santo Domingo before. When I mentioned Alex, Chadd remembered him well. “Wow! He must be a teenager by now!” Alex had been engaging outsiders for a while. Carlos said Alex was always at the guesthouse when Carlos was in town. I told the students they would have some time now to work in small groups to come up with a way to study this phenomenon and reject or support one or more hypotheses. I gave them about 15 minutes and each group then presented their research ideas. I recorded all of the presentations. This post is getting a little long and I want to finish strong, so I won’t go into detail on these presentations, but but here’s a screenshot. I’ll send full videos to anyone who wants to see them.

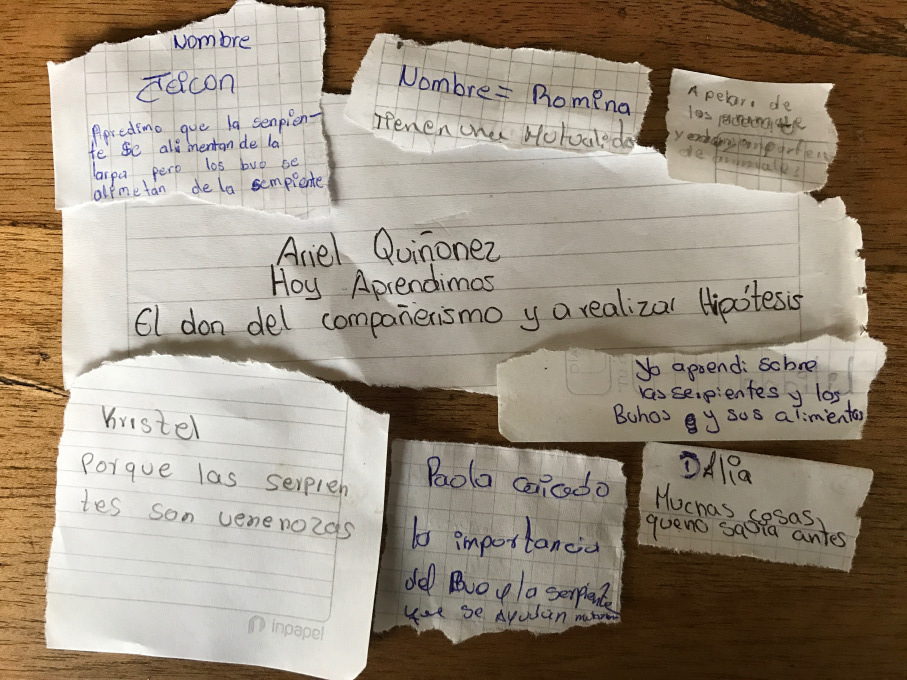

I told the students they would have some time now to work in small groups to come up with a way to study this phenomenon and reject or support one or more hypotheses. I gave them about 15 minutes and each group then presented their research ideas. I recorded all of the presentations. This post is getting a little long and I want to finish strong, so I won’t go into detail on these presentations, but but here’s a screenshot. I’ll send full videos to anyone who wants to see them. The students took the request for a “piece of paper” quite literally. They tore pieces from their books, even taking tiny pieces from blank pages. Some reached over and tore off a piece of someone else’s piece. Some of the pieces fit together like a jigsaw puzzle as you can see in one of these pictures. That night, Lucia and I looked through them. As I generally suggest my student teachers do, I made piles of similar responses. I usually have one pile for students who seemed to understand what we were doing and gave me the responses that I generally anticipated. An example of this is Jabes who wrote, “The snakes that the owls carry to the nest are for the sake of the chicks to benefit from the snakes.” Jabes understood the ecological concept that one organism might benefit from its association with another. I usually have another pile for students who I might assess as either not being engaged in the lesson, not understanding the point, or not being able to express themselves well. Kristel’s response, “Because the snakes are venomous,” falls into this category.

The students took the request for a “piece of paper” quite literally. They tore pieces from their books, even taking tiny pieces from blank pages. Some reached over and tore off a piece of someone else’s piece. Some of the pieces fit together like a jigsaw puzzle as you can see in one of these pictures. That night, Lucia and I looked through them. As I generally suggest my student teachers do, I made piles of similar responses. I usually have one pile for students who seemed to understand what we were doing and gave me the responses that I generally anticipated. An example of this is Jabes who wrote, “The snakes that the owls carry to the nest are for the sake of the chicks to benefit from the snakes.” Jabes understood the ecological concept that one organism might benefit from its association with another. I usually have another pile for students who I might assess as either not being engaged in the lesson, not understanding the point, or not being able to express themselves well. Kristel’s response, “Because the snakes are venomous,” falls into this category. The purposes of the trip were to learn about the people of Santo Domingo and their culture, to observe and teach in classrooms in the school, Gaston Figueroa, and to lead professional development workshops for the teachers. We had no contact with the outside world, except in emergencies. This was challenging for me, but it gave me lots of time to think and take notes, to read, to teach, and to talk to amazing people, both on the trip with me and in the town. It has also meant that it has taken some time for me to process the experience. I have posted pictures, but haven’t really figured out how to write about it until now. It was a little overwhelming coming from Santo Domingo back home and it took a while to process everything. The longer I wait, however, the more my memory fades. I have some notes, but a lot I didn’t realize I should write down until later. So these stories will by their nature be only narratives: my recollections and interpretations of what happened.

The purposes of the trip were to learn about the people of Santo Domingo and their culture, to observe and teach in classrooms in the school, Gaston Figueroa, and to lead professional development workshops for the teachers. We had no contact with the outside world, except in emergencies. This was challenging for me, but it gave me lots of time to think and take notes, to read, to teach, and to talk to amazing people, both on the trip with me and in the town. It has also meant that it has taken some time for me to process the experience. I have posted pictures, but haven’t really figured out how to write about it until now. It was a little overwhelming coming from Santo Domingo back home and it took a while to process everything. The longer I wait, however, the more my memory fades. I have some notes, but a lot I didn’t realize I should write down until later. So these stories will by their nature be only narratives: my recollections and interpretations of what happened.

The guesthouse was buzzing with kids. Alex was there: charming, bright, andenthusiastic, bantering with Carlos and anyone else. I don’t remember how it started, but I had been thinking that I hadn’t been able to use scientific notation that day. I started to show Alex how to do some simple problems, which he caught onto very quickly, remembering exponents. I explained about the size of the atom, and how this was a way to express it without writing out so many zeroes.

The guesthouse was buzzing with kids. Alex was there: charming, bright, andenthusiastic, bantering with Carlos and anyone else. I don’t remember how it started, but I had been thinking that I hadn’t been able to use scientific notation that day. I started to show Alex how to do some simple problems, which he caught onto very quickly, remembering exponents. I explained about the size of the atom, and how this was a way to express it without writing out so many zeroes.

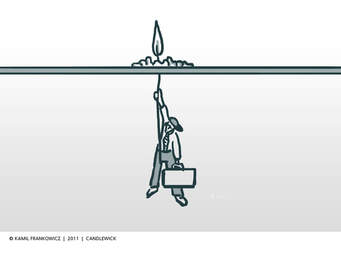

Students play the roles of Aristotle, Plato, and Democritus observing a phenomenon in which a boiling “cauldron” is then topped with a transparent “lid”. They prepare for and engage in philosophical dialogue and then ice is added. The dialogue continues after that. The setup looks a little like this but with a glass plate instead of Saran Wrap.

Students play the roles of Aristotle, Plato, and Democritus observing a phenomenon in which a boiling “cauldron” is then topped with a transparent “lid”. They prepare for and engage in philosophical dialogue and then ice is added. The dialogue continues after that. The setup looks a little like this but with a glass plate instead of Saran Wrap. In this report, I describe my visit Willam M. Botnan School in Aldea Santa Avelina, in Quiche, Guatemala with Teachers2Teachers International. William M. Botnan has 137 students total in the primary grades. There are sixty students in the pre-primary grades. There are two other schools that are pre-primary/primary in Santa Avelina. There is one other that is just pre-primary. The primarily language in Santa Avelina is Ixil (ee—sheel), a Mayan language. Most people learn Spanish by the time they reach first grade. A few people can speak a little English.

In this report, I describe my visit Willam M. Botnan School in Aldea Santa Avelina, in Quiche, Guatemala with Teachers2Teachers International. William M. Botnan has 137 students total in the primary grades. There are sixty students in the pre-primary grades. There are two other schools that are pre-primary/primary in Santa Avelina. There is one other that is just pre-primary. The primarily language in Santa Avelina is Ixil (ee—sheel), a Mayan language. Most people learn Spanish by the time they reach first grade. A few people can speak a little English. Participate in a [model] lesson where the

students think and speak while the teacher

listens [and responds].

Participate in a [model] lesson where the

students think and speak while the teacher

listens [and responds]. In our early team discussion about Santa Avelina, I had been told to expect a very reserved, polite group who would sit down and talk quietly. My personal style is to move about the room, usually bubbling with enthusiasm. In most cases I can’t help myself, because I get excited. But in this case, I was restrained, and we sat together at a set of desks discussing the pendulum question. (A nice feature of William N. Botnan is that the desks are all whiteboards.)

In our early team discussion about Santa Avelina, I had been told to expect a very reserved, polite group who would sit down and talk quietly. My personal style is to move about the room, usually bubbling with enthusiasm. In most cases I can’t help myself, because I get excited. But in this case, I was restrained, and we sat together at a set of desks discussing the pendulum question. (A nice feature of William N. Botnan is that the desks are all whiteboards.) might think of arguing as negative. We don’t really enjoy

hearing two brothers arguing over who has to do a chore, for

example. But arguing in science has a purpose of bringing us to

greater understanding.

might think of arguing as negative. We don’t really enjoy

hearing two brothers arguing over who has to do a chore, for

example. But arguing in science has a purpose of bringing us to

greater understanding. On Sunday, July 5, Li Qin, Rachel, and I returned to Chongqing from Chengdu with a big week

On Sunday, July 5, Li Qin, Rachel, and I returned to Chongqing from Chengdu with a big week

The professional development is handled at the level of the district, as it is

The professional development is handled at the level of the district, as it is with us, but the teacher leaders appear to have a lot more autonomy. These teacher leaders were the people who came to every talk, workshop, or class I did. They seem to be the people in China who are most like me; people trying to soak up every good thing they can about science teaching. These pictures are from the last day of my class later that week, but a bunch of the people in them are teacher leaders who had been at the Huaxin talk and workshop on Monday.

with us, but the teacher leaders appear to have a lot more autonomy. These teacher leaders were the people who came to every talk, workshop, or class I did. They seem to be the people in China who are most like me; people trying to soak up every good thing they can about science teaching. These pictures are from the last day of my class later that week, but a bunch of the people in them are teacher leaders who had been at the Huaxin talk and workshop on Monday.

The name comes from the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 BCE), a relatively long-lasting dynasty in Chinese history, and one under which art and music developed abundantly and there was significant expansion of influence.

The name comes from the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 BCE), a relatively long-lasting dynasty in Chinese history, and one under which art and music developed abundantly and there was significant expansion of influence. the Marquis Wuhou, (武侯祠 ). It is a set of temples, statues, and gardens dedicated t Liu Bei (161-223),

the Marquis Wuhou, (武侯祠 ). It is a set of temples, statues, and gardens dedicated t Liu Bei (161-223), Emperor of the Kingdom of Shu in the Three Kingdoms period, and Zhuge Liang (181-234), prime minister of the kingdom. It was supposedly begun around 1,800 years ago when Liu Bei’s mausoleum was first built in 223 AD. The modern site mostly dates from the early Ming dynasty (17th century).

Emperor of the Kingdom of Shu in the Three Kingdoms period, and Zhuge Liang (181-234), prime minister of the kingdom. It was supposedly begun around 1,800 years ago when Liu Bei’s mausoleum was first built in 223 AD. The modern site mostly dates from the early Ming dynasty (17th century). have

have this deep, shared identity that is connected also to the land. It must be like belonging to one large family that has continued to inhabit the same homestead. I was surprised to learn from my young Chinese friends that most of them don’t know anything about their families beyond their grandparents. Maybe this is just because they’re young and they don’t have that yearning yet to “Know Where I Come From”. Or maybe they do know where they come from. They come from China. They come from the Han. Maybe if you Know Where You Come From it’s not as important to find out more.

this deep, shared identity that is connected also to the land. It must be like belonging to one large family that has continued to inhabit the same homestead. I was surprised to learn from my young Chinese friends that most of them don’t know anything about their families beyond their grandparents. Maybe this is just because they’re young and they don’t have that yearning yet to “Know Where I Come From”. Or maybe they do know where they come from. They come from China. They come from the Han. Maybe if you Know Where You Come From it’s not as important to find out more.

I posted this picture in my post on tea and coffee. These guys were always hanging out in groups on side streets in Beibei, Chongqing, Jiangbei, and Chengdu. I’m not a dumb guy, but it never crossed my mind to wonder why they were hanging out there. Finally, on my last day, and with Rachel’s help, I figured out that they were motorcycle-taxis. They wait there until someone comes looking for a fare. There are also little red three-wheeled taxis too. I did not see one woman driving any of the three types of taxis, but I did see many women on little scooters (especially in Chengdu) and occasionally driving motorcycles. Kitty and the students never took the motorcycles or the little red taxis–only the official yellow ones in Chongqing and green ones in Chengdu. I asked Rachel why not. “Too dangerous,” she said. I think the people I hung out with are stable enough financially to afford to ride in the respectable taxis, because I saw many people riding on the back of these motorcycle taxis–often with two people piled on back and usually, when it was raining, carrying an umbrella.

I posted this picture in my post on tea and coffee. These guys were always hanging out in groups on side streets in Beibei, Chongqing, Jiangbei, and Chengdu. I’m not a dumb guy, but it never crossed my mind to wonder why they were hanging out there. Finally, on my last day, and with Rachel’s help, I figured out that they were motorcycle-taxis. They wait there until someone comes looking for a fare. There are also little red three-wheeled taxis too. I did not see one woman driving any of the three types of taxis, but I did see many women on little scooters (especially in Chengdu) and occasionally driving motorcycles. Kitty and the students never took the motorcycles or the little red taxis–only the official yellow ones in Chongqing and green ones in Chengdu. I asked Rachel why not. “Too dangerous,” she said. I think the people I hung out with are stable enough financially to afford to ride in the respectable taxis, because I saw many people riding on the back of these motorcycle taxis–often with two people piled on back and usually, when it was raining, carrying an umbrella. Knife Gorge this past Friday. I saw this many times, but it was often difficult to capture a shot. There are actually two women on the back of this motorcycle, clinging on tight and carrying the umbrella.

Knife Gorge this past Friday. I saw this many times, but it was often difficult to capture a shot. There are actually two women on the back of this motorcycle, clinging on tight and carrying the umbrella. Women dress in a lot of different styles, but a very common thing (at least in the summer in Southwest China) is to wear short (very) skirts with high-heeled wedges like these. You’ll see a young woman, in a short skirt and wedges, holding a parasol, and riding side-saddle on one of those motorcycle taxis, weaving its way in and out of traffic in Beibei, presumably on her way to work or class.

Women dress in a lot of different styles, but a very common thing (at least in the summer in Southwest China) is to wear short (very) skirts with high-heeled wedges like these. You’ll see a young woman, in a short skirt and wedges, holding a parasol, and riding side-saddle on one of those motorcycle taxis, weaving its way in and out of traffic in Beibei, presumably on her way to work or class. earlier post “The People”. On our last day in Jinli, I took a walk in the early morning back through the enormous park that connected Jinli to the Wuhou Shrine and watched people walking, playing badminton and ping pong, doing Tai Chi, Kung Fu, and Qi Gong, massaging themselves around the head and neck, and dancing. You would see people of both sexes doing these things, and with dancing, you’d see men and women dancing together and women and women dancing together. I didn’t see men dancing together. Here’s a picture from when Kitty and I went looking for an open coffee shop in Beibei last Wednesday. (We couldn’t find one that opened before 11 and ended up back in Kitty’s office–hear more complaining about this in my post on tea and coffee).

earlier post “The People”. On our last day in Jinli, I took a walk in the early morning back through the enormous park that connected Jinli to the Wuhou Shrine and watched people walking, playing badminton and ping pong, doing Tai Chi, Kung Fu, and Qi Gong, massaging themselves around the head and neck, and dancing. You would see people of both sexes doing these things, and with dancing, you’d see men and women dancing together and women and women dancing together. I didn’t see men dancing together. Here’s a picture from when Kitty and I went looking for an open coffee shop in Beibei last Wednesday. (We couldn’t find one that opened before 11 and ended up back in Kitty’s office–hear more complaining about this in my post on tea and coffee). You also are very likely to see women walking together on the street holding hands or with arms

You also are very likely to see women walking together on the street holding hands or with arms linked, but not men. (Although I did capture this picture to the right–must’ve been something pretty

linked, but not men. (Although I did capture this picture to the right–must’ve been something pretty